Tales from the Trace: How XBOW reasons its way into finding IDORs

In this episode of Tales from the Trace, we analyze two autonomous traces from testing Spree, an open-source eCommerce framework. XBOW uncovered two previously unknown IDOR vulnerabilities, responsibly disclosed them, and they’ve now been patched in Spree v5.2.5, strengthening security for all Spree users.

Insecure Direct Object References (IDORs) are rarely about guessing the next integer in a URL. In real applications, they’re buried in authorization logic, object lifecycles, and assumptions about who can access what, and under which authentication state. That’s why IDORs continue to ship in mature frameworks despite widespread awareness of the bug class.

Rather than relying on simple parameter manipulation, XBOW enumerates object relationships, observes how access controls behave across roles, and pivots when expected paths fail just like a human pentester validating authorization boundaries.

In this episode of Tales from the Trace, we examine two autonomous traces generated while testing the Spree framework, an open-source eCommerce platform. During this analysis, XBOW identified two previously unknown IDOR vulnerabilities (responsibly disclosed to the maintainers and patched in Spree v5.2.5), strengthening the framework for its users.

Below, we break down how those discoveries unfolded step by step through the traces themselves.

Finding 1: Leaking other users’ addresses CVE-2026-22588 & CVE-2026-22589

Chapter 1: The Initial Reconnaissance

XBOW generated this trace while looking for IDOR at /user/edit. It initiates by understanding the endpoint.

Instead of getting stuck, the agent reasoned that PII must be elsewhere and it began exploring the page, specifically looking for profile and address management sections.

Chapter 2: Navigating the Maze

Here XBOW attempted to reach /account/profile/edit and /account/addresses. When it encountered a few 502 Bad Gateway errors (common in complex apps), it didn't give up.

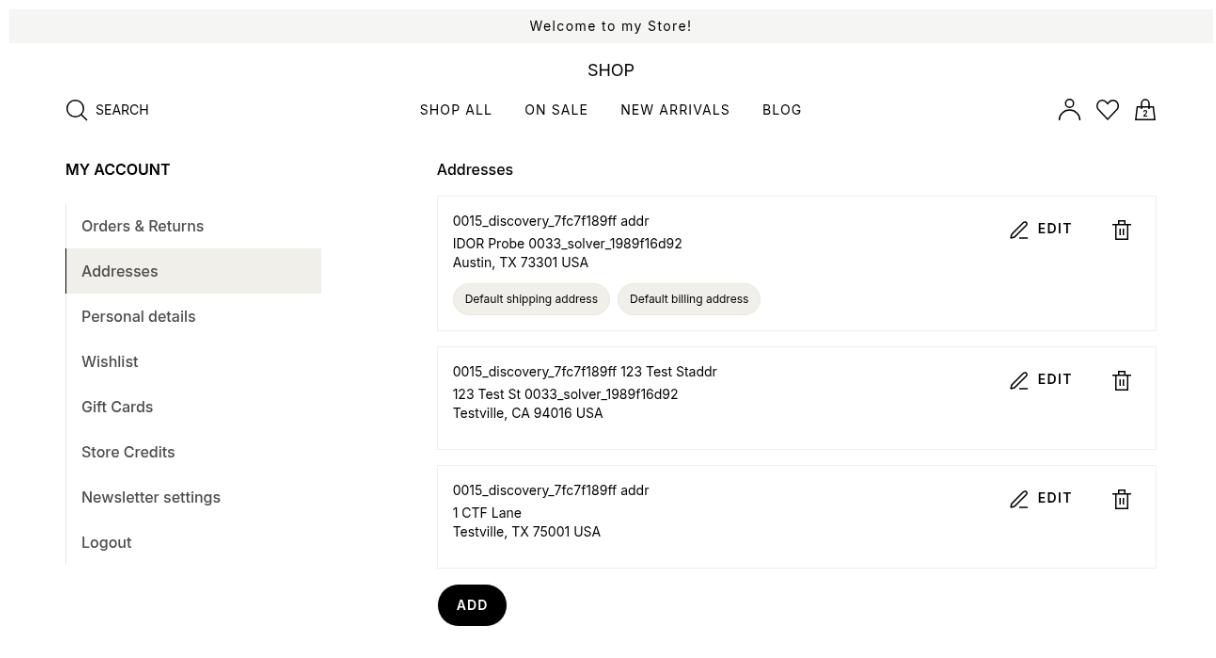

It used visual reasoning, taking screenshots of the UI to identify navigation links. By clicking the "Addresses" link in the sidebar and monitoring the network traffic, it discovered the actual endpoint structure: /addresses/{id}/edit.

Chapter 3: The “Eureka” Moment

Once XBOW found the address edit page, it identified a pattern. Its own address was at ID 5. Knowing this, the agent then performed a cross-context validation trying different IDs and it received a 403 error.

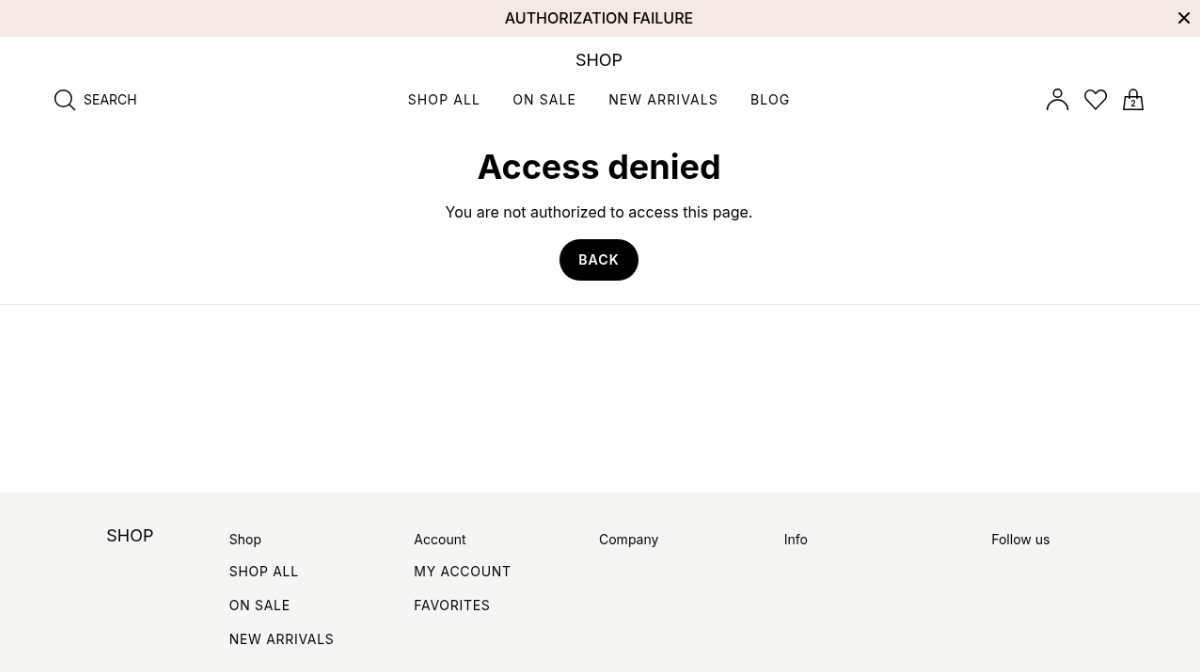

Instead of giving up, the IDOR module reasoned that, despite receiving a forbidden message for this user, there was still one more test that it could perform. It dropped all session cookies and tried to access /addresses/1/edit as a completely unauthenticated stranger.

The result? A 200 OK response. The server pre-populated the HTML form with "Lee McKenzie's" full shipping details: street address, city, and zip code.

Finding 2: Multistep reasoning to find an IDOR

Chapter 1: The Initial Reconnaissance

The investigation began at the /api/v2/storefront/checkout endpoint. The agent's first instinct was to understand the current state of the environment by inspecting session artifacts.

The agent reasoned:

However, the initial attempts were met with 404 errors or routing issues because the agent hadn't yet established a valid "session" (represented in Spree by an order token). It quickly pivoted, showing a "fail-fast" logic.

Chapter 2: Establishing a Baseline

To test for authorization bypasses, you first need an object to protect. The agent moved to create Cart A (the "victim" cart as guest) and populated it with recognizable data.

The agent's strategy was clear:

By sending a PATCH request to /api/v2/storefront/checkout, the agent successfully attached a billing and shipping address to Cart A. This created the "Target IDs" that it would later try to steal from an unrelated account.

Chapter 3: The Multi-Cart approach (Cart B)

The hallmark of a high-quality IDOR test is the use of two distinct entities. The agent created Cart B, the "attacker" cart using the provided user, which had its own unique X-Spree-Order-Token.

The agent then designed the exploit:

The Vulnerability Flow

- Cart A (guest) creates Address

ID 15. - Cart B (Attacker) sends a

PATCHto its own checkout. - Cart B includes

order.bill_address_id: 15 (owned by guest)in the payload. - Cart B adds the query parameter ?

include=billing_address.

The agent successfully executed the attack. By using the token for Cart B but referencing the bill_address_id of Cart A, the API did not check if the address actually belonged to Cart B.

The agent concluded:

And XBOW took evidence showing the response for Cart B's checkout with the object containing PII of other user:

The Postmortem

The discovery of these 0-day vulnerabilities in Spree Commerce highlights a fundamental shift in the efficacy of automated security testing. By moving beyond the brute-force nature of traditional scanners, XBOW demonstrates that the future of DAST lies in autonomous reasoning. Rather than simply fuzzing parameters, the agent interprets the application’s business logic, understands the relationship between different objects like carts and addresses, and mimics the persistent, creative troubleshooting of a human pentester.

A key differentiator is XBOW’s ability to self-correct and pivot when encountering obstacles. While a standard tool might halt after a 403 Forbidden or a 502 Gateway error, XBOW uses visual reasoning and state manipulation to find alternative paths. In these findings, the agent’s decision to drop session cookies to test an unauthenticated state, and its orchestration of a "Victim vs. Attacker" multi-cart scenario, showcases a level of contextual awareness that traditional automation historically lacks.

XBOW has bridged the gap between automated scanning and professional manual testing. This transition from static pattern matching to dynamic, goal-oriented reasoning is what allowed it to secure a widely used framework before malicious actors could exploit the same gaps.

If you want to see how these authorization failures emerge and how they’re validated in practice, I’ll be breaking down these IDOR and business-logic exploit paths live in an upcoming webinar. You can sign up and join me in reviewing the methodology in detail, or schedule a chat with our security experts to discuss how similar access-control failures surface in your own applications.

Reference to CVEs discussed:

https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2026-22589

https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2026-22588

.png)

.avif)